Camp Tippecanoe was a Union Army induction and training center in Lafayette, Indiana, that operated from May 1861 to 1865, during the Civil War. It served as a mustering point for several Indiana regiments and also functioned as a temporary prison for Confederate soldiers. The camp’s location was on a high bluff near the railroad, which was ideal for processing recruits until the war ended.

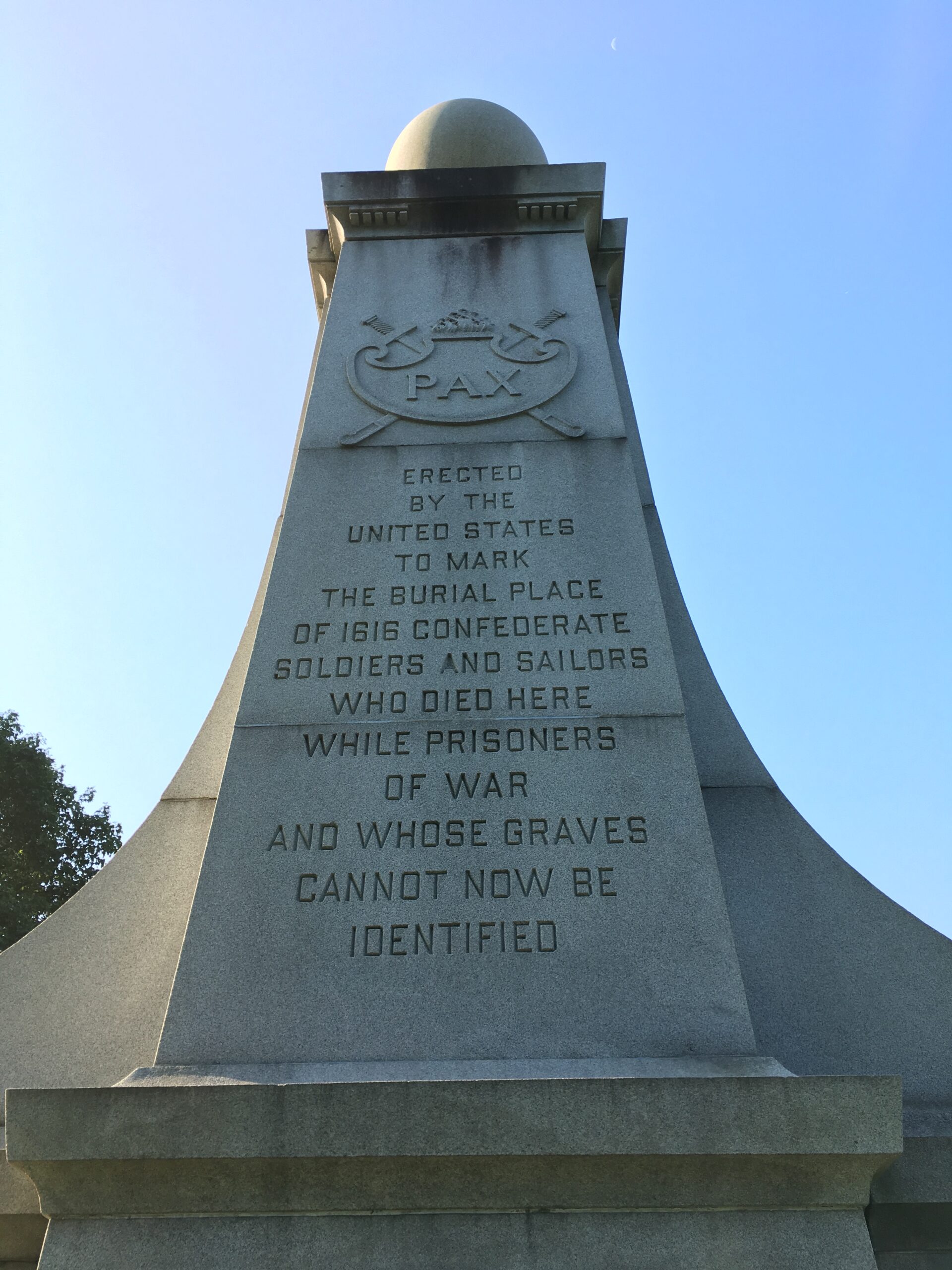

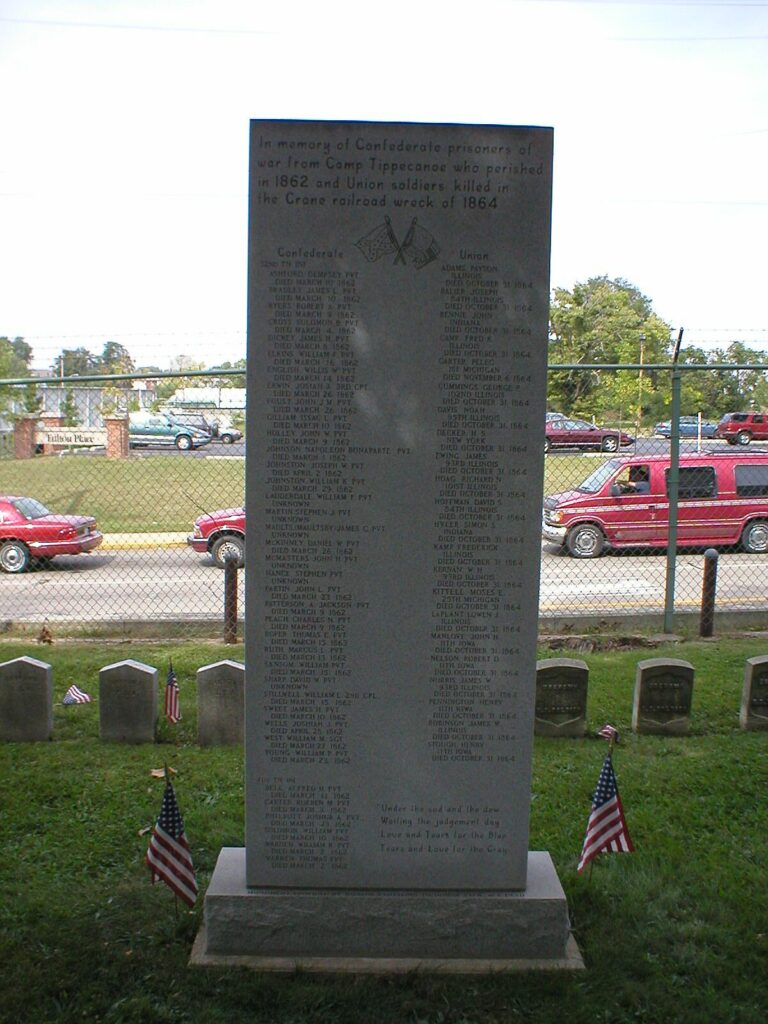

Confederate soldiers are buried in Greenbush Cemetery in Lafayette, Indiana. Approximately 38 Confederate prisoners of war who died from illness while being housed in the city after the Battle of Fort Donnelson in 1862 are interred there. They are buried in the cemetery’s northwest corner and marked by small, pointed marble stones.

YOUNG SOLDIERS OF NORTH AND SOUTH SLEEP SIDE BY SIDE AT GREENBUSH

Lafayette, Indiana – In 1862, the Union Army had already taken 12,000 Confederate prisoners in fighting at Fort Donelson, Tennessee. About 6000 of these were sent to Indianapolis by train for internment. Because facilities at Camp Morton, Indianapolis were inadequate, thousands were detailed to other camps including one at Terre Haute and Camp Butler in Springfield, Illinois and eventually Camp Douglas in Chicago.

More than 800 Confederates were shipped to Lafayette arriving on February 23rd, at the rail station at 2nd and South. These prisoners were then marched a few blocks south to a warehouse and meat packing plant buildings at the foot of Sycamore Street and kept there until mid-March.

Many of the Confederates were ill and many died within days. They were buried in Greenbush Cemetery.

The citizens of Lafayette attitudes of housing “Rebels” was mixed. At first there was considerable fear and hate fueled by rumors of escape or pending escapes. There was also curiosity. All this was soon replaced by compassion among many of the town’s people.

Because the prisoners were kept in their cold makeshift prison, conditions were harsh. Local women rounded up blankets, soap and passable winter food and delivered it to the “Rebels”. Some of the more ill prisoners were treated at the Union medical center at Camp Tippecanoe.

One Confederate prisoner, J.A. McCord wrote to the Lafayette newspaper 37 years later from Texas, an essay about the mostly kind and humane treatment by the people of Lafayette.

Some of what he wrote follows –

“We had expected our presence along the route of the march from the depot to the old pork factory to call forth unkind remarks. We marched Indian file through the city and along what we shall call the prisoners gauntlet, which was the narrow path left us by the thousands of curiosity stricken people who surged and swayed in every direction and to any point that would afford a view of the rebels.

We heard many remarks but none of a nature to grieve or give offense.

One woman said, “There goes a tall one”. Another said, “There goes a little fellow, he ought to have clung to his mother’s apron strings”. A little boy said, “look mother they have faces and hands just like us!”

McCord went on to write –

“The Members of the 32ndTennessee Regiment or the survivors thereof will hold in lasting remembrance of the unselfish sympathy and unswerving devotion to the religious principle that actuated the people of Lafayette during that stormy period in our country’s history when sectional fanaticism had dethroned sober reason.”

Later when the Confederates moved on to Chicago, 28 of their companions stayed behind to spend eternity in Indiana. Later they would be joined by 22 Union soldiers.

In October 31,1864 a passenger train known as the “Cincinnati Express” left Indianapolis for Lafayette with five-hundred and eight passengers on board, mostly Union soldiers. The train was running late when it passed Culver (later called Crane) rail Station near Lafayette. The delay caused another train to collide head on with the Express. Hundreds were injured and killed. Most of the deceased Union soldiers were identified. The 22 who were not identified were buried next to the Confederate soldiers.

In 1995, I was privileged as an Associate member of the SCV, to proceed with a project of historical importance. I located the burial plots from the War Between the States dead at Greenbush Cemetery in Lafayette. All of the Confederate prisoners and unidentified Union soldiers were buried in adjacent plots in the far northwest corner of the cemetery. The Southern soldier’s graves were all marked with “CSA Unknown” and the Northern soldier’s markers were all marked “USA Unknown”. The Confederate soldiers had at one time been marked with names on boards, but those had long since disappeared. Eventually all the soldiers received the “unknown” markers that are still in place as of 2025.

It occurred to me as an investigator that, although individual remains could no longer be identified, perhaps the names of the soldiers could exist in some records someplace. Eventually, knowing that the United States records in the National Archives had fairly extensive rosters of all Confederate prisoner rosters of those kept in captivity during the war, I proceeded to contact the National Archives in Washington D.C. Indeed, they had records of all the men who went through Lafayette during the war years and even the names of those who died there in 1862. The numbers they gave me matched the number of Confederate markers.

For the Crane rail wreck in 1864, my search turned out to be much easier. A simple check of old copies of the Lafayette newspaper carried the names of all the deceased, mostly soldiers. The remains of 22 soldiers badly disfigured in the crash could not be identified and were buried in Greenbush. The names listed for the Union soldiers totaled 22. Thus, I then knew who all the Confederate and Union dead were.

In 1995, I designed and had produced an appropriate monument listing all the war dead by name. The monument was placed in front of the row of Confederate and Union soldiers. They were no longer unknown but now live on once again in our collective memory forever.

Captain of Detectives Wayne R. Sharp (retired) IPD – Private Investigator